By Kyle Thede, SC&A intern and Public History graduate student

In the spring of 1942, only months into the United States’ involvement in World War II, the Army Air Forces were taking steps into uncharted territory. While Britain’s Royal Air Force had deployed night fighters (with limited success) in the closing stages of the Battle of Britain, the practice had remained an experimental pursuit for America. Efforts to develop suitable airborne radar had been undertaken and refined ever since English ground-based radar had proved ineffective in coordinating aerial combat, and the U.S.’s first purpose-built night fighter, Northrop’s P-61 Black Widow, was still in the design and prototyping stages. As a stopgap measure, both Britain and America converted a number of Douglas’ DB-7 “Havoc” (“Boston” to the British) light bombers using newly developed radar equipment as well as powerful Turbinlite searchlights.

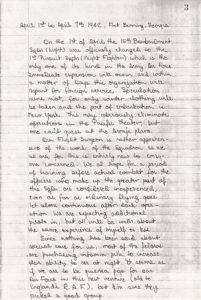

At the beginning of April, William C. Odell found himself in the midst of these preparations while posted at Fort Benning, Georgia, as a Havoc pilot in the 15th Bombardment Squadron. Only days before he and his squadron-mates were due to set sail from New York, the 15th was re-organized into the 1st Pursuit Squadron, the first such unit in the Army Air Forces to specialize in night fighting. It wasn’t a transition that came naturally for the squadron personnel. The new night fighter training program involved hundreds of hours of both ground school and flying courses specializing in some of the most demanding tasks that can be asked of an airman, such as blind landings, navigating in the dark, and enemy aircraft recognition. Little wonder, then, that Odell noted in his diary that “it seems as if we are to be guinea pigs for our Air Force in this new venture.”

Night fighting also presented a medical challenge in addition to the obvious technical ones. Odell’s diary remarks that the squadron’s Flight Surgeon was “rather apprehensive” about the whole undertaking, and that most of his comrades increased their vitamin intake to help improve their night vision. This anxiety came on top of the fact that, despite being only days away from deployment, the Army Air Forces’ first night fighting unit had no idea where they were actually going. The Pacific seemed the least likely theatre, since the squadron only packed winter clothing for the trip ahead, but as Odell pointed out, “one can’t guess at the Army’s plans.”

As it turned out, the 1st Pursuit Squadron’s foray into the developing field of night fighting didn’t even last through the end of the transatlantic voyage to their eventual destination, England. En route, the unit was reverted to its original light bombing role, and attached to VIII Bomber Command upon their arrival. Still, the re-re-named 15th Bombardment Squadron, although no longer the first of its kind, managed to earn another historical distinction of note. On July 4, 1942 – Independence Day – flying borrowed RAF Boston bombers alongside those of the British 226 Squadron, aircrews from the 15th flew the first Army Air Force bombing raid to hit Axis-occupied territory, striking four Luftwaffe airfields in the Netherlands. The American air war over Europe had begun.

Sources:

Maurer, Maurer. Combat Squadrons of the Air Force, World War II, edited by Maurer Maurer, Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1982.

McFarland, Stephen L. Conquering the Night. Air Force History and Museums Program, 1998.

Odell, William C., diary entry, April 1st-7th, 1942, MS-120, box 1, file 13.